3 steps to making any yoga pose more effective: why do we repeat the pose before we hold it

2“Raise your hand if you are busy” – my teacher Gary Kraftsow likes to prompt at his workshops. This always gets the same reaction – a short disbelieving laugh, as in “Who isn’t?” Yes, we are all busy, so our time matters. This applies to our yoga practice as well. Every yoga pose we do needs to matter; it needs to be effective for our bodies, our physiology and our mental state. How do we do that? This is what we will focus on today (Hint: It DOES NOT involve holding poses indefinitely).

But before we present those 3 steps to a more effective yoga practice, let’s define how the body is affected by movement (or lack of it).

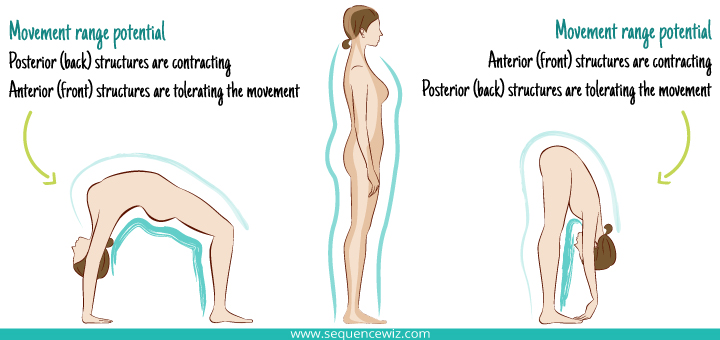

The human body is generally capable of an incredible range of motion. Just look at how far forward and how far back you can potentially bend (keeping in mind that even from birth the maximum range will differ from person to person).

An image above is an example of the relationship between the anterior (front) structures of the body linked by fascia, and posterior (back) structures that are linked by fascia as well. When there is a balanced relationship between the front and the back of the body, it remains upright effortlessly and is capable of both deep back bending and deep forward bending. When you bend backward, the muscles in the back contract and the tissues at the front allow for the backbend to happen because they have high tolerance for this sort of pull (thank you Jules Mitchell for this excellent term). Tolerance basically means that both your tissues and your nervous system give the green light to this intense pull at the front and don’t freak out about it. Bending forward will test the tolerance of the posterior (back) structures.

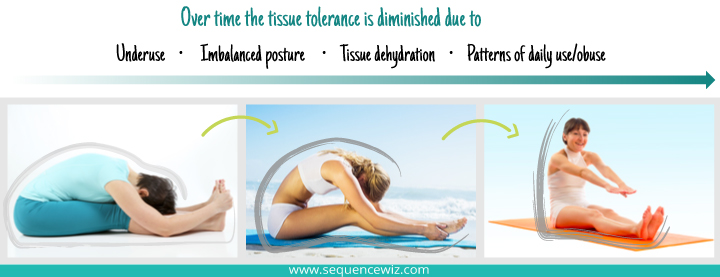

Over time, however, things change. Since our daily activities do not require such extreme ranges, our body’s tolerance for such movements begins to diminish. Add to that poor posture, tissue dehydration, and repetitive patterns of daily use, and you will see that your range of movement gradually shrinks. What it means is that when you attempt a deep forward bend, the tissues in the back of the body will scream: “No, no, no, stop!”, because they no longer have the same tolerance for movement.

By itself it’s neither here nor there – so what if you cannot put your chest on your thighs in a forward bend. It becomes problematic when it creates an imbalance in the body, for example, pulls you into a “military posture”, which then continues to reinforce the tension in the posterior (back) structures. This will continue to pull your body out of balance, create additional stress on the tissues and eventually manifest as pain.

In our yoga practice we are attempting to restore the tissue tolerance (willingness to adapt) back to it’s original potential (or close to it) for the purpose of releasing of the chronic holding patterns. And this is how we do it.

3 steps to making any yoga pose more effective

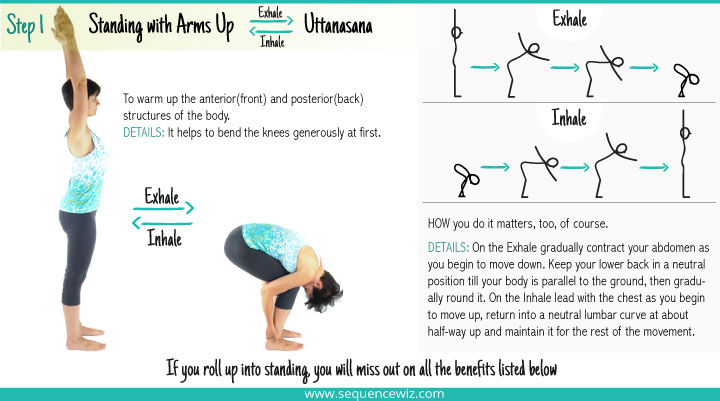

Step 1. Move in and out of the pose between the neutral position and the maximum comfortable range.

By moving in and out of the pose we increase circulation to larger skeletal muscles and surrounding tissues. Muscles are designed to contract and relax in succession; doing repetitive movements in a yoga practice helps us to

- Dynamically warm up the body

- Lubricate your connective tissues (fascia, joints, ligament, etc.)

- Minimize the risk of injury

- Develop healthy muscle tone

- Release chronic muscle contraction

- Improve range of motion at the joint level.

Moving in and out of the pose also gives us an opportunity to observe and modify our habitual movement patterns. Our bodies change to reflect the activities and movements that we do most often, which over time can lead to imbalance and pain. If we do yoga poses without awareness of our own patterns of movement, we reinforce those patterns, continuing on the vicious cycle. Moving in and out of the pose several times helps us notice the potentially dysfunctional pattern, and then change it the next time we move into the pose. The proper scientific phrase for that is “neuromuscular reeducation”. This is the most direct way to affect how we use our bodies in our daily activities. If those patterns remain unchanged, they will continue to cause problems.

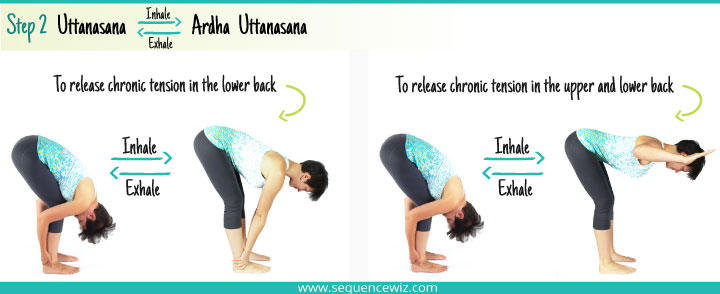

Step 2. Move into the maximum range of the pose and then work on contracting and releasing the target area at this end point.

In Step 1 we were concerned with general warm-up and movement patterns, while in Step 2 we begin the actual process of restoring tolerance to it’s original potential both on the level of tissues and your nervous system. By alternatively contracting and relaxing the muscles while deep in the pose, we are training your body and your mind to recognize and accept this new position. This is where the actual release of chronic muscle contraction happens.

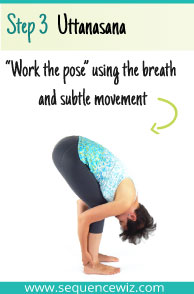

Step 3. Holding the pose statically.

Holding the pose statically after repeating it few times sends the signal to your body and your nervous system that this range of movement is acceptable. It helps “cement”, so to speak, the work that we’ve done in Steps 1 and 2. While holding the pose, it is essential to use the breath properly and “work the pose” with subtle movements; practicing this way leads to a more profound physical, physiological and psychosomatic transformation. This will be our topic of our next conversation. Read it here >

[jetpack_subscription_form]If this article makes sense to you, please spread the word!

Thank you for this article and all the eye opening information on your site! I am so grateful I came across it, I look at my practice in a whole new light now.

Thank you Jen! I am so happy to hear that this is useful to you!