When “good posture” is not so good for your body

3 “Sit up straight!” my dad would command every time he saw me lean over my desk. And I would jerk myself up trying to maintain “good” posture. The problem was that my thoracic spine was already rather flat, which means that in my effort to sit up straight I would over compensate and assume a “military posture” which over the years created a lot of tension in my upper back and neck. I see this overcompensation pattern in my students all the time. An effort to have a good posture is noble and certainly useful to the body but figuring out what that “good posture” is for YOUR body can be tricky.

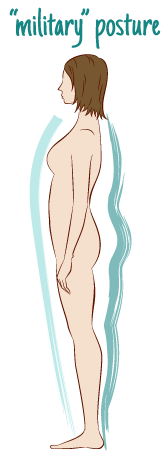

“Sit up straight!” my dad would command every time he saw me lean over my desk. And I would jerk myself up trying to maintain “good” posture. The problem was that my thoracic spine was already rather flat, which means that in my effort to sit up straight I would over compensate and assume a “military posture” which over the years created a lot of tension in my upper back and neck. I see this overcompensation pattern in my students all the time. An effort to have a good posture is noble and certainly useful to the body but figuring out what that “good posture” is for YOUR body can be tricky.

When we had a conversation about core strength and stability we mentioned how important the spinal curves are. We have them for a reason – they help us distribute the weight of the heavier parts of the body within gravitational pull. The cervical curve is necessary to support the weight of the head; thoracic spine balances out the weight of the rib cage and the head above it, and the lumbar spine negotiates the relationship between the pelvis and all the structures above it. We need all three curves, although the degree of the curvature varies from person to person and is mostly congenital (with some acquired modifications). We need those curves, yet for some reason we are intent on getting rid of them. We do a lot of shoulder stands and begin to lose the cervical curve; we try to avoid “slouching”, assume a military posture and begin to lose the thoracic curve; we sit a lot and tuck the tailbone under habitually and begin to lose the lumbar curve.

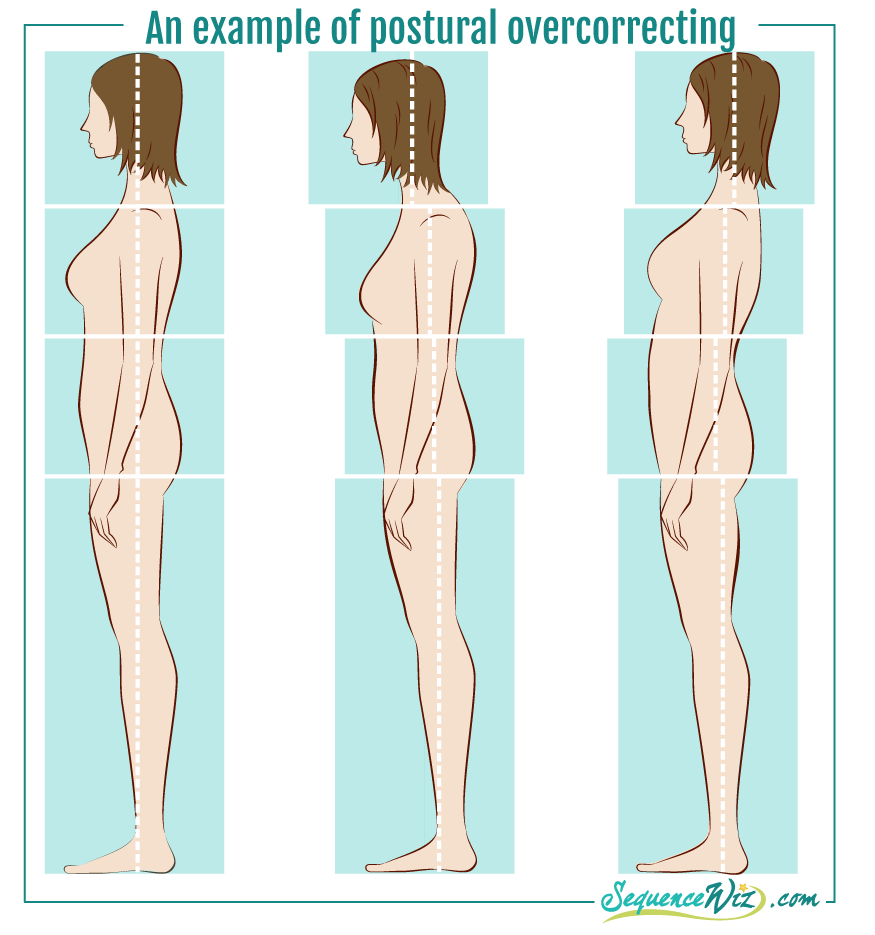

Many yoga students I see are concerned about their posture and try to “self-correct” by intentionally rearranging the positioning of their body parts. For example, if someone’s head is displaced in front of the body, the student might insist on pushing it back; if somebody thinks of their posture as “slouchy” she might intentionally pull the shoulders back, and so on. Unfortunately there are several issues with this type of self-correcting:

1. A student’s perception of her body positioning might not match the reality.

2. Students often don’t have a sense of where those repositioned body parts should end up.

3. Students often forget that all spinal curves affect each other – if you change the position of one of them, the others will change shape as well to compensate for the new alignment.

So this type of mechanical rearrangement of different body parts is rarely useful; what works much better is the idea of lengthening up in the hope that the spinal curves will naturally stack on top of each other.

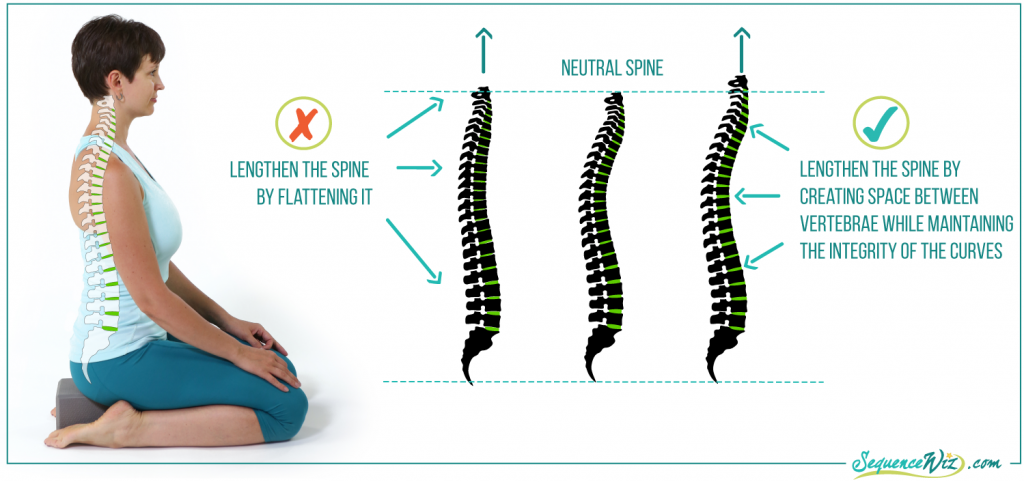

In yoga we talk a lot about “lengthening the spine” – what does it mean exactly? A student might interpret it as an invitation to pull the top of the head and the tailbone in two opposite directions and maximally flatten all spinal curves in the process – while in reality what we are trying to do here is to create space between the vertebrae while maintaining the integrity of the spinal curves. This might seem like it’s the same thing, but in reality it is a complete change in prospective.

Let’s try a quick experiment. Wherever you are right now, close your eyes and follow this 3-minite spinal awareness exercise (don’t do it while driving or on treadmill, of course 🙂 ).

This guided practice shows you two different ways of lengthening your thoracic spine. You can do similar things with your cervical and lumbar spine, too.

The distinction between spinal flattening and creating space between vertebrae is important in any pose, but it is crucial for maintaining a comfortable meditation posture. Often in their effort to remain perfectly upright the students end up putting unnecessary stress on the postural muscles, which means that they come out of meditation with aching bodies. Focusing on creating space between the vertebrae while maintaining the integrity of the spinal curves puts much less strain on the muscles and is easier to maintain throughout the meditation practice.

In general we try to lengthen the spine in any posture, whether it’s a forward bend, back bend or a twist. Lengthening the spine usually allows us to go deeper and be more comfortable in any pose; it also makes most poses safer. And, of course, gravity is constantly pulling us down (we always go to bed shorter then we are when we wake up) and we try to counteract that constant pull by lengthening upwards. Yet there is a special category of poses where we specifically work with the idea of spinal lengthening – in viniyoga we call those axial extension postures. The poses that fit into that category might seem very different at the first glance – Bird dog, Downward facing dog, Easy pose – but they are all united by the common purpose – to lengthen the spine along its axis. Next week we will begin our exploration of axial extension poses – tune in!

Hi Olga,

A great article as always. I appreciate your research and eloquence of presenting it. I find that axial extension isn’t always the only problem that students can deal with. The individual that sits in front of a computer for 8 or 9 hours at work and then several more hours at home can have very interesting back problems. Weakness in the abdominal muscles and uneven tightness in the chest and shoulders are at play.

Standing or sitting up straight can be lost in their personal awareness. I would love to see your take on addressing this issue.

Best wishes to you and your family for a Happy Holiday and wonderful New Year.

Georgeanna

Hi Georgeanna! I completly agree – there are many other issues associated with posture. We will be talking about some of them in the future. 🙂 Happy Holidays to you as well!

Love this, thank you for explaining it so clearly.