How the brain can interpret other signals as pain

2One of my clients has recurring knee issues. For her, there is always a low degree of discomfort that never goes away; sometimes it flares up, causing sharp pain. When that happens, she tends to get very scared, worrying that knee pain would affect her walking (which is very important for her sense of independence and balanced mental state). She calls herself “knee-rotic” because she recognizes that she can be a bit neurotic about her knee pain.

As we discussed last week, this is the result of the brain’s negativity bias – the tendency to expect and prepare for the worst.

“In general, the default setting of the brain is to overestimate threats, underestimate opportunities, and underestimate resources both for coping with threats and for fulfilling opportunities. Then we update these beliefs with information that confirms them, while ignoring or rejecting information that doesn’t.”(1)

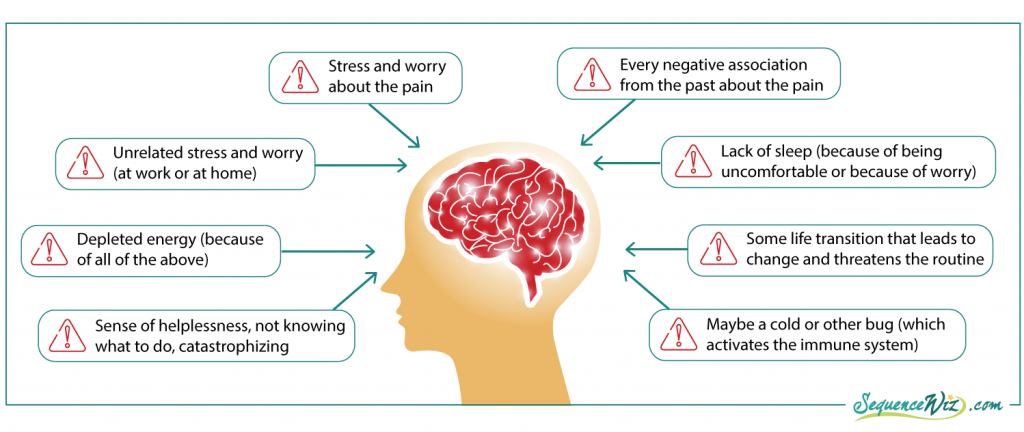

So any time your brain detects a physical threat, it goes on alert (“flashes red”) as it mounts a response. If the experience is familiar and is deemed non-threatening, it switches back to “green mode” as the healing process progresses. But if the experience is unfamiliar, without a clear trigger and without obvious management strategies, the brain can get stuck in the “red mode” and become over-reactive. Any other perceived threats that come up (even if entirely unrelated to the issue at hand) will continue to pile up and make matters more complicated. It goes something like this:

Knee injury (or wear-and-tear) occurs![]() Nerve endings in the knee become sensitive and might misinterpret other sensations for pain

Nerve endings in the knee become sensitive and might misinterpret other sensations for pain![]() Brain begins to overreact to the slightest sign of similar sensations and becomes vulnerable to other stressors

Brain begins to overreact to the slightest sign of similar sensations and becomes vulnerable to other stressors![]()

All of these factors send alert signals to the brain that eventually start to blend together and the brain begins to interpret one as the other. Any new sensation in the knee gets interpreted as pain; feeling stressed gets interpreted as pain; a sense of helplessness gets interpreted as pain, and so on. All of this happens separately from the actual process of healing that takes place in the knee and is not necessarily connected to it.

So if you focus on targeting the knee pain with strictly physical measures like strengthening the surrounding musculature, for example, it will have a very limited effect. That’s why statements that abound in the yoga world like “this pose is good for knee pain” do not carry much weight. Yes, certain poses might help strengthen the muscles that support the knee; but it will not necessarily help with knee pain. Luckily, yoga tradition is uniquely suited to address chronic pain. Why and how? Let’s explore >

References

References

Hardwiring Happiness: The New Brain Science of Contentment, Calm, and Confidence by Rick Hanson, Ph.D.

I really appreciate this post. I am a fairly new yoga teacher and I have recently suffered a serious foot injury (non-yoga related) and have been diagnosed with CRPS, a nerve disorder all about nerves misinterpreting normal sensations. My world has turned upside down as I try to learn to let go of the “pain” that is a misinterpretation while listening to the pain that is a result of the injury. I have had to stop teaching temporarily (as well as a great deal of my asana practice). I think when I go back I will be a different teacher. I look forward to more posts on this subject.

This is a very interesting series. In addition to being a yoga teacher, I’m a clinical psychologist. Today’s post in particular reminded me of the sequelae similar to what occurs with panic attacks. (For example, in that cycle, the tiniest of physical symptoms becomes feared as something going wrong, which amplifies it further, which sets off more anxiety and more physical symptoms, etc., etc.)

Looking forward to your next installment!