How to work with chronic pain on the level of physiology (part 1)

3Some days when I begin my yoga practice I can feel the entire physical history of my body: here is that neck tension from staring at the computer all day yesterday, and here is that old hamstring injury from an unfortunate split, and here is that wonky sacrum… Every body carries the history of past injuries and hurts, but most of the time your brain chooses not to get alarmed about it and those experiences of past pain do not rise to the level of a full-blown pain episode.

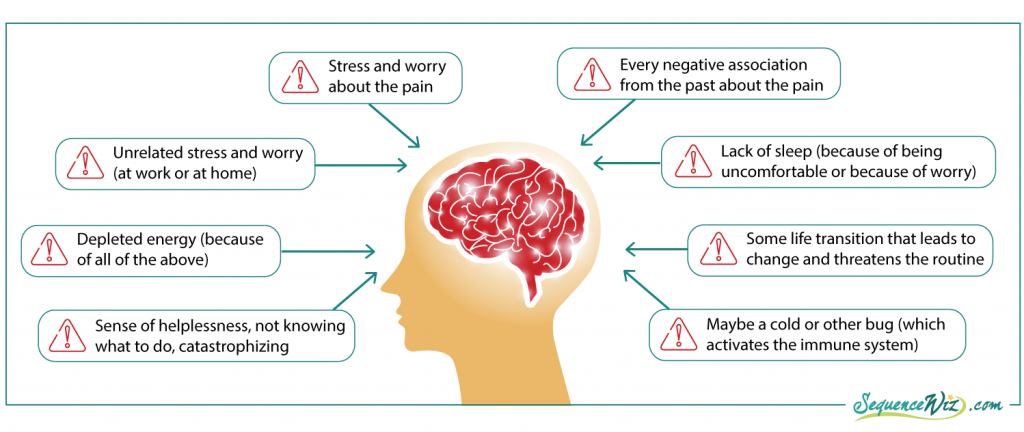

Other times your brain decides to be alarmed about a certain sensation based both on past experience of similar sensations and current context. The situation gets exacerbated by other unrelated factors and can lead to a full-blown emergency pain-and-stress response.

The emergency stress response initiates a cascade of physiological changes in the body; it consists of:

The emergency stress response initiates a cascade of physiological changes in the body; it consists of:

1. Endocrine response (release of adrenaline to initiate and amplify sympathetic activation);

2. Sympathetic system activation (a branch of an autonomic nervous system responsible for fight-or-flight or freeze response in emergency situations);

3. Immune response (increased inflammation to heal wounds and fight toxic invaders).

Having recurring emergency responses for every suspicious sensation in the body is very taxing on the entire system (and, needless to say, generally unpleasant). What can we do about it? We certainly cannot control how much adrenaline gets dumped into our blood stream, but we can control one aspect of our physiology that gives us access to sympathetic/parasympathetic balance. It’s the breath.

Breath both REFLECTS the inner state of your body and AFFECTS it. When your sympathetic system gets activated, you might experience a classic fight-or-flight response with the body mobilizing all resources to fight or flee. As a result your breathing becomes fast, it happens mostly in your chest, and you can even hyperventilate. Or you might experience sympathetic activation as “freeze” response, when the body withdraws to protect itself from the painful experience, which can show up as holding the breath, breathing in shallow or incomplete way, and overall difficulty with breathing.

It becomes a vicious cycle where the emergency response breathing pattern persists even after the emergency had passed and continues to send signals to the brain that the danger is still present. To get out of this cycle we need to change the breathing pattern to promote parasympathetic activation (rest-and-digest mode), and reassure the brain that all is well and healing is underway.

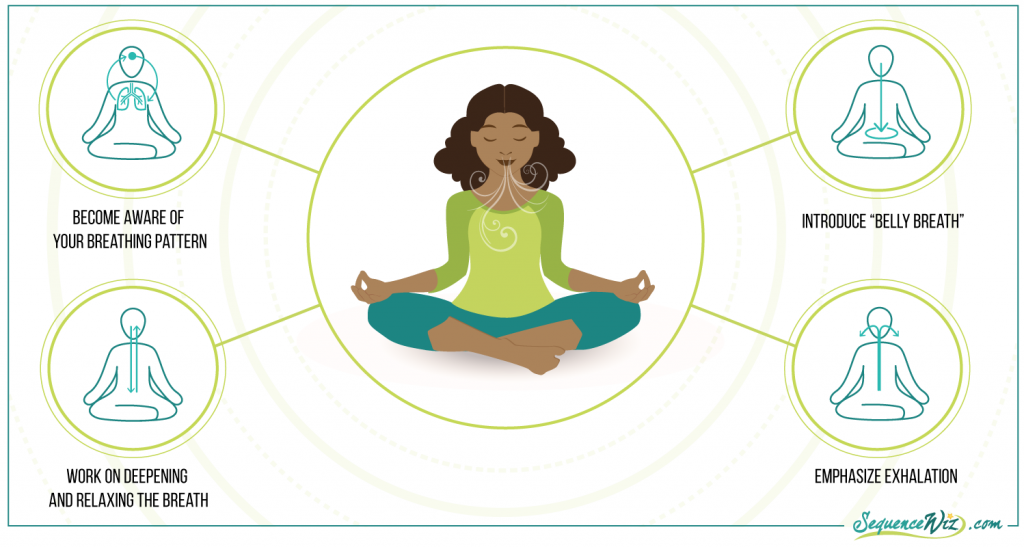

The starting points of working with breath for chronic pain management are:

Step 1. Become aware of your breathing pattern. You cannot consciously change something that you are not aware of. So the first step is to notice your habitual breathing patterns, especially during a pain episode. Do you tend to breathe fast, do you tend to hold your breath or does your breath become shallow? At any point of the day, bring your attention to your breath and observe it for few cycles. Simply bringing your attention to your breath might help calm your system down.

Step 1. Become aware of your breathing pattern. You cannot consciously change something that you are not aware of. So the first step is to notice your habitual breathing patterns, especially during a pain episode. Do you tend to breathe fast, do you tend to hold your breath or does your breath become shallow? At any point of the day, bring your attention to your breath and observe it for few cycles. Simply bringing your attention to your breath might help calm your system down.

Step 2. Work on deepening and relaxing the breath. Deepening the breath has all sorts of physiological benefits for the entire system. In terms of sympathetic/parasympathetic balance, “when your breathing is relaxed, your nervous system receives the message that you are safe and well. This message ignites a cascade of changes in your body and mind that can prevent or interrupt a full emergency pain-and-stress response. The result is that you immediately feel better, while teaching the mind and body a healthier way to respond to pain and stress.”(1)

Step 3. Introduce “belly breath”. When the sympathetic system is activated, you are more likely to take shallow breaths that happen mostly in the chest. Intentionally expanding your belly out on the inhale AS IF you were breathing into your belly has a grounding and calming effect on the entire system.

Step 4. Emphasize exhalation. Every time you inhale you activate your sympathetic system a bit and every time you exhale you activate your parasympathetic system. That is why emphasizing long flowing exhalations helps facilitate the “rest-and-digest” response and turns off the alarms in your brain.

For any breathing techniques to have an effect, it is recommended to do it for at least 12 breath cycles. Not all practices will work for all people. The breath should never be forced.

In the short run, simple breathing practices can effectively calm down the nervous system and help lessen the pain; in the long run healthy breathing patterns help make the brain less reactive to minor instances of pain. Breath work becomes more impactful with consistent practice over time.

Next week we will talk about the three pillars of physiological balance and how we can use yoga to make sure that they are functioning properly. Tune in!

Resources

Resources

- Yoga for Pain Relief by Kelly McGonigal, Ph.D.

Hi Olga, pain and our breath’s influence, what an interesting topic! In my classes, I often have the impression that even there, people don’t breath deeply. I believe that happens as a consequence of conditioning. I encourage my participants to deepen the breath, especially the exhales, but I’m wondering how to emphasize breath work beside Nadi Shodana. What do you do to help your students focus more consciously on their breath?

Hi Stefanie! I completely agree it’s so easy for students to go back to their default breathing patterns, even in a yoga class. And when we ask them to “take a deep breath” it means different things to different people. One of my former clients who was an ear-nose-throat doctor used to tell me that when he asks his patients to take a deep breath they just gulp the air in. So in viniyoga tradition we use the principles of ratio to make sure that students truly try to deepen their breath. I would start as class inviting students to inhale for 6 seconds and exhale for 6 seconds. Giving it a specific number encourages students to deepen their inhale and lengthen their exhale. Then you can come back to it in the course of the practice, reminding them to inhale for 6 and exhale for 6. As the practice progresses you can even go to 8 and 8. Another thing that I notice often is that students do not finish their inhale before they begin to exhale and vice versa. So cues like “Please finish your inhale and then exhale slowly” might be useful. You can also ask them to hold the air in (or out) for couple of seconds; this also helps separate inhale from exhale and make sure each one is complete. These are just some simple ideas that you can use. I wrote a post about ratios a while back, you might find it useful. Hope this helps!

Thanks for sharing, Olga! That was a good point taking it further. A specific number helps, I think. I like the thought of paying attention to finishing the inhale, pausing, exhaling slowly. I just had a quick look at your post, and it looked interesting; I’ll check it out in a calm moment.