How to deal with your daily ups and downs: The four R’s of restoring connection

13Couple of months ago my husband and I went to see a play. It ran long, we hit traffic on the way back home, and instead of being away for three hours, as expected, we were running about 15 minutes late to relieve our babysitter. We stopped by the ATM to get some cash for her, and my husband got out $30 saying that since we were only 15 minutes late, it wasn’t a big deal. I was firm that we needed to get $40 to round up to the next hour. He actively resisted. I blew up. We ended up getting $40 and arguing all the way home. We paid the babysitter $40, but the conflict was not resolved.

Later I was reflecting on what had set me off so strongly on this particular occasion. My husband’s position was pretty clear – he believes that people should be paid exactly what was agreed upon, rounding up mathematically to the nearest hour. For me though, it’s an entirely different story. When I look at my babysitter, I see myself in her. I see a young woman who didn’t have much money, but had drive and perseverance to work hard, acquire skills and get somewhere in life. I see her at the beginning of that journey, the journey that I went through myself, while being supported and uplifted by respect and generosity of older women. I would not dream to nickel-and-dime other young women, I feel like now it is my turn to be generous and supportive. The mere idea of disrespecting her time and effort was infuriating to me, but I had hard time articulating it in the moment, and my husband ended up on the receiving end of it all.

Afterwards, when I was done stewing in my rage, I was wondering why I couldn’t just explain calmly how unacceptable it was to me. And then I read this quote by Deb Dana from The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy that made it perfectly clear. She writes: “To expect a person to access the qualities of social engagement when they are caught in a neuroception of danger or life-threat is futile. The ventral vagal pathways [that guide friendly social connection] are biologically unavailable.” Even though I was not in actual physical danger, my deep beliefs felt threatened, and inevitable sympathetic fight-or-flight reaction followed (I chose to fight via arguing first, then flee by giving my husband a silent treatment :).

But this quote also opens up the door for us to recognize the physiological nature of our reactions, and develop some compassion toward ourselves, our loved ones and our students, who sometimes seem to have disproportionate reactions to the most mundane events or words.

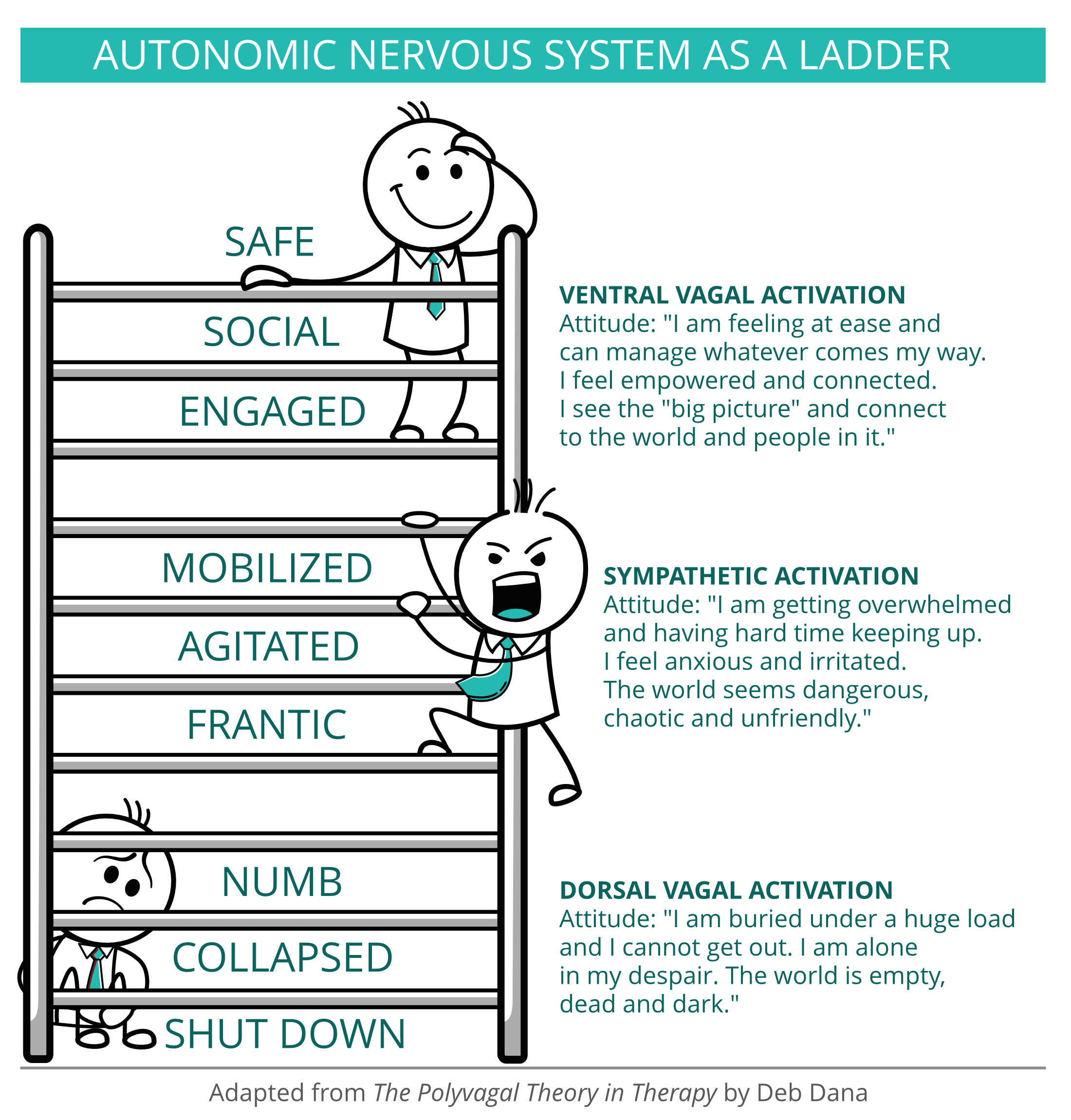

From the perspective of Polyvagal Theory, whenever we have a strong reaction to something, it is our autonomic nervous system trying to protect us from a perceived threat. We can sense it in ourselves and others as “being defensive”, and it can manifest as becoming withdrawn (dorsal vagal state) or openly combative (sympathetic state).

What do we do about it? How do we climb out of those states and back up the ladder toward ventral vagal state (safe, connected, receptive and social)? Deb Dana outlines the four R’s that move us up the ladder and restore the state of connection:

1. Recognize the autonomic state

When you are having a strong reaction to something, the first step is to acknowledge that you are having a physiological response to a trigger. That response is highly individual: “Autonomic patterns are built over time. The autonomic nervous system is shaped through experience. In response to experiences of connection and challenge, we develop a personal neural profile with habitual patterns of action. Recognizing these responses and seeing the patterns of activation is the first step in polyvagal-informed practices.”(1) If you are able to simply observe your physiological reaction (increased heartbeat, feeling of heat, sweaty hands, tense muscles, etc.) without lashing out, you move it from the realm of neuroception (physiological detection of a threat) to actual perception (consciously acknowledging your unease).

2. Respect the adaptive survival response

“Through a polyvagal lens, we understand that actions are automatic and adaptive, generated by the autonomic nervous system well below the level of conscious awareness. This is not the brain making a cognitive choice. These are autonomic energies moving in patterns of protection. And with this new awareness, the door opens to compassion.”(1) When you (or your loved one, friend, student, etc.) flip out, this simply means that your autonomic nervous system is doing its job of protection. Instead of fighting it, the best course of action is to respect it for its diligence, and maybe even express some gratitude for it, as in “Wow, thank you for defending me.”

3. Regulate or co-regulate into a ventral vagal state

Once the acute physiological response has passed, you can work on bringing yourself up to the social, peaceful state. To be able to do that, you would usually need three things: internal abilities, environmental safety and social support.

- Cultivating internal abilities means developing reflective self-consciousness about your reactions and a bag of tricks that reliably make you feel better. This bag of tricks can include doing a yoga practice, going for a walk, singing along to a favorite song, cuddling with your dog, and so on. Different tricks will be more appropriate for different states. For example, if you are feeling angry, it might be better to release that energy by doing something more active, and when you are feeling withdrawn or depleted, it may be better to snuggle with your dog. Different things work for different people. You need to know what works for you.

- Creating environmental safety means creating a comfortable environment where you feel safe and at ease. Sometimes it is as obvious as moving away from a potentially violent situation, and other times it can be much more subtle. How comfortable do you feel in your office, in your car, in your home? Are you surrounded by people and objects that feel nourishing or draining? Sounds, smells, other people’s energy, temperature – they all contribute to the sense of safety in your environment. It helps to analyze how you feel in spaces where you spend most of your time and make corrections, if necessary. For example, I do not feel good when I sit at my computer with an open door behind me. I do not know why that is, I can make up a story about it, but ultimately, I know that closing the door simply makes me feel better.

- Seeking social support means cultivating positive relationships through work alliances, enduring friendships, intimate partnerships. We are wired to connect. “When opportunities for connection are missing, we carry the distress in our nervous system. Our loneliness brings us pain.”(1) We rely on other people to help us regulate our emotional states on the level of physiology. Those relationships need to be reciprocal, with equal give-and-take over time, otherwise they become draining.

4. Re-story or re-frame

“Humans are driven to want to understand the “why” of behaviors. We attribute motivation and intent and assign blame.”(1) We create stories about why we feel the way we feel, and why we do what we do. These stories can keep us in a constant defensive state, or they can help us feel safe and receptive. Ultimately, it’s about convincing our automatic nervous system that it’s OK to let the defenses down. In the example at the very beginning of this post, the initial story that followed my agitated state was “My husband is arguing about nonsense, he wants a flight.” After I recognized my state, acknowledged it, and went for a walk to manage it, my story changed to: “I am reacting defensively because my deep beliefs feel threatened, even though it was not at all his intention.” Once you change your narrative, you can move out of the defensive state and become able to reconnect and trust other people again.

To summarize, in dealing with our daily ups and downs, it is useful to recognize that autonomic response is constantly being activated as a defense mechanism. If we recognize this visceral response, we move from “being in” to “being with” our experience. Bringing awareness to our automatic responses allows us to observe them, embrace them for their protective power, and open a door to possibility of deeper inquiry into our reactions. Once we become curious and introspective about our own reactions, we move into ventral vagal state, where exploration, self-inquiry and open-mindedness are possible.

Next week I will be sharing some short lessons from the Polyvagal Theory that I think are particularly useful to yoga teachers and yoga therapists. Follow me on Instagram (@ok.yoga) to check them out and to share your opinion!

[jetpack_subscription_form]

References

1. Deb Dana The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy

I love this! Great article. Thank you!

Thank you Jennifer!

I liked the line ,noticing the difference between, “being in” to “being with” experience.

For me, the difference is being unaware or awake and aware. That takes allowing for allowing space for a Pause, in order to “feel”.

I think that this is a great way to describe this Karin. Thank you for sharing!

Thank you for such a clear explanation ??

Thank you!

Thank you Olga – your intuitive post has encouraged me to look deeper into the polyvagal theory!

Yey! I hope you find it as fascinating as I did.

I am loving this series of articles around the ANS! You have a keen ability to merge conversational and pedantic writing together, and I am learning so much. Thank you and keep them coming!!

So wonderful to read this series of blogs and insights! Thank you!

Great information to share, Olga! I’m both a psychologist and a yoga teacher, and I’ve been learning more how to use polyvagal theory in my work with clients and in my yoga teaching, too.

I”m late to the party, but someone shared this link with me after I had a rough weekend fighting with my spouse. I realized after I read it *why* I was feeling unsafe… thank you for posting it.

Thank you, Mary Kate; I am so glad to hear that the article resonated with you!