The mechanics of inhalation and the proper way to inhale in yoga

2In college I majored in Russian literature, and I remember being fascinated by the sheer number of heroines in the Russian classics who would faint at the slightest sign of distress. After all, I never knew a single person who ever fainted from an emotional disturbance. But now I wonder if the ladies in those books simply couldn’t breathe, wrapped up in their corsets. Restricted rib cage movement and lack of abdominal expansion pushed their inhalation into the chest, producing the effect of a heaving bosom, so vividly and admiringly described by many writers. Add to that a little hyperventilation from hearing some unfortunate news and boom, you are on the floor (or fainting couch).

Thank goodness we left corsets in the past – that was definitely not a healthy way to breathe. But even now, there is no consensus in the yoga world about what kind of breathing is best. You will hear that chest breathing is bad, or that belly breathing is bad, and that diaphragmatic breathing is best. Do we breathe from chest to belly or from belly to chest? I actually find that often in those discussions we are not even talking about the same things.

Sometimes, when folks talk about diaphragmatic breathing, they portray it as opposite to chest breathing, for example. This is a curious and not necessarily accurate juxtaposition. Every inhalation is diaphragmatic – we cannot inhale without moving the diaphragm. Sometimes the movement of the diaphragm might become restricted (for different reasons), and if that happens, other accessory muscles have to step up and work harder (causing exaggerated chest movement, lifting of the shoulders, tensing of the neck, etc.). This is called shallow or costal breathing. Generally, we are trying to avoid shallow breathing. However, this is not the same thing as chest breathing in yoga. Chest breathing does not equal heaving or shallow breathing. Today let’s try to figure out the mechanics of inhalation and the proper way to inhale in yoga.

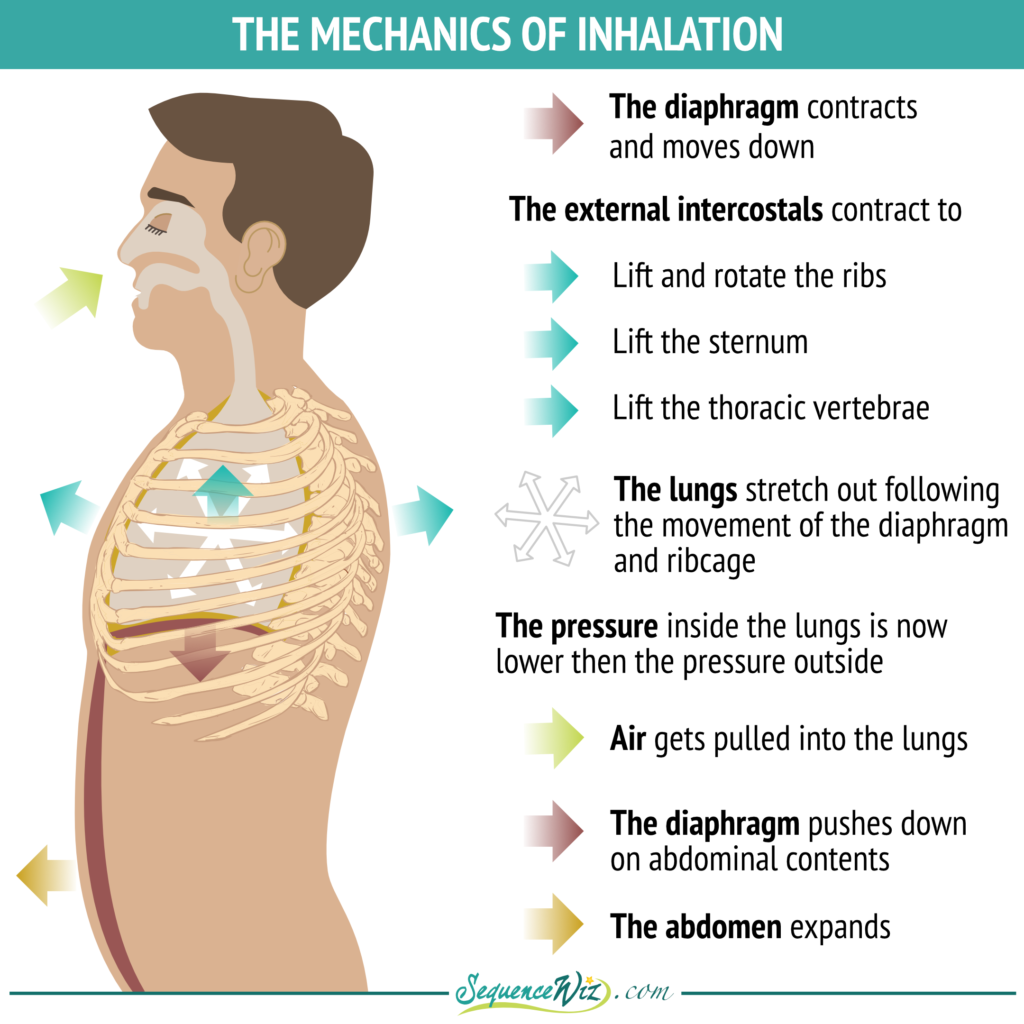

First, let’s take a look at what happens physiologically when you breathe in:

- Diaphragm contracts and moves down (your diaphragm is responsible for 75% of inhalation);

- External intercostal muscles contract, lifting and rotating the ribs, lifting the sternum slightly, and lifting the thoracic vertebrae a bit;

- Belly expands because the contents of the abdominal cavity get squished by the diaphragm from the top and need to protrude somewhere.

Physiologically, all of that happens at the same time, there is no directionality to this movement (top to bottom or bottom to top).

In yoga we might choose to ride one or more of those actions ON PURPOSE, to achieve a particular effect. We might choose to emphasize:

- Movement of the diaphragm (to increase awareness and tonicity of that muscle),

- Lifting of the sternum, which results in chest breathing (to stretch the chest, prepare for back bending postures and create an uplifting effect throughout the system),

- Expansion of the rib cage (to deal with ribcage stiffness, increase lung compliancy and create an uplifting effect throughout the system),

- Lengthening of the spine, particularly thoracic spine (to create space between the vertebrae, to promote better posture, the imagine upward movement of energy, to prepare for axial extension postures, to sense the central axis of the body),

- Expansion of the belly, which results in belly breathing (to emphasize the downward movement of the diaphragm, retrain students from holding the belly in and to promote a grounding effect on the system).

Your breathing will still be diaphragmatic, but you are adding different flavors to your breath, depending on what you are trying to accomplish. We can also add directionality to our breathing. On the inhale we can choose to:

- Expand chest first, then expand the belly,

- Expand belly first, then expand the chest,

- Practice radiating breath from the center outward.

All of those patterns are accomplished by intentional muscular engagement and movement of awareness. Each one of those patterns produces a slightly different physiological and mental-emotional effect; none of them are right or wrong, or more natural than others.

That’s the beauty of yoga – you can choose a particular flavor of diaphragmatic breathing to augment and enhance a particular movement practice. For example, if you plan to focus on exploring backbends in your practice, you might choose to emphasize chest breathing; if you want to use the image of the mountain in your practice as a symbol of stability and permanence, you can use belly breathing to enhance it; if you plan to demonstrate the outward movement of energy in poses like Half Moon, you can use radiating breath to illustrate that idea.

With so many breathing options available, things might get pretty complicated. That is why it also helps to have a default breathing option that is familiar and useful to your students in most situations. In viniyoga tradition, the default breathing pattern for inhalation is chest to belly. This means that on the inhale we encourage our students to expand the chest (and entire rib cage) first, and then expand the belly from the navel down to the pubic bone. We use this pattern of inhalation because it:

With so many breathing options available, things might get pretty complicated. That is why it also helps to have a default breathing option that is familiar and useful to your students in most situations. In viniyoga tradition, the default breathing pattern for inhalation is chest to belly. This means that on the inhale we encourage our students to expand the chest (and entire rib cage) first, and then expand the belly from the navel down to the pubic bone. We use this pattern of inhalation because it:

- Helps to deepen and lengthen the inhale,

- Increases awareness of all structures involved in inhalation (rib cage, diaphragm, abdomen),

- Helps improve tonicity of the diaphragm,

- Helps support better posture,

- Follows the intuitive flow of breath from the nose down,

- Has a balancing energetic effect,

- Facilitates the downward movement of Prana,

- Works well with the preferred method of exhalation (which we will discuss next week).

We also often use the image of spinal elongation on inhalation, but not because the spine naturally lengthens with inhalation (there is usually only a subtle movement in the thoracic portion because of rib rotation). We do it because one of the fundamental ideas of viniyoga is that we use breath to animate the spine. That way we closely link the breath to the subtle movement of the spine, which serves as a bridge between the physical and energetic dimensions. That way, your breath is no longer an afterthought to your movement, but the driving force. We start by connecting to our breath, then we use the breath to create subtle movement in the spine, then we extend that subtle movement of the spine into larger movements of extremities (arms and legs). If you are able to establish that connection, every movement you make becomes much more organic and intimately linked to your breath.

It is entirely up to you which pattern of inhalation you choose for yourself and your students. Just remember that it has less to do with what happens physiologically when you inhale, and more to do with what kind of purpose you assign to your practice. Next time we will talk about the qualities and techniques of exhalation – tune in!

[jetpack_subscription_form]

Beautifully clear and concise as always, thanks Olga 😀

Thank you, great article ??