The mighty heart: How your circulatory system nourishes every cell in your body

4“Go to your bosom; Knock there, and ask your heart what it doth know.”– wrote William Shakespeare. We expect a lot from our metaphorical hearts. We want them to know what’s true, love deeply, feel compassion, point us in the right direction, give us peace and clarity, and, in general, enable us to live authentically and fully. We don’t expect the same from our kidneys, for example.

In reality, our physiological heart has only one job to do: it has to pump. It does this job really well, pumping about 70 gallons of blood every hour (!), all day, every day, without a break, for as long as we are alive. This is not an easy job: the heart must pump with enough force to bring the blood all the way down to the extremities AND all the way back up against gravity. The heart manages it remarkably well; the journey of blood around the body takes about fifty seconds to complete. Why all the commotion? Why does the heart need to move the blood around so swiftly? It’s because circulating blood carries nutrients, oxygen, and chemical instructions and provides a way to remove waste to each of the roughly 75 trillion cells in your body. This system is so efficient that none of your cells are more than five cells away from a blood vessel. The blood also tracks down and kills pathogens. These services are so essential that a body region deprived of circulation dies in a matter of minutes.

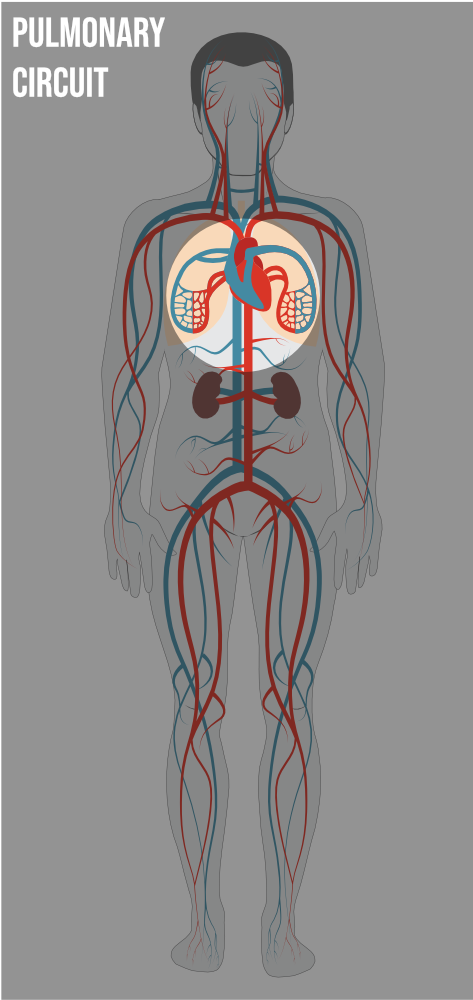

That’s a lot of responsibility for an organ that’s the size of a fist and weighs less than one pound. It is small but mighty; it never rests. The heart is actually two pumps, not one: one pump (which drives the pulmonary circuit) sends blood to the lungs, where blood is oxygenated, and the second pump (which drives the systemic circuit) sends the oxygenated blood around the body. In the pulmonary circuit, oxygen-depleted blood from the body enters the right side of the heart and then travels to each lung through the right and left pulmonary arteries. In the lungs, carbon dioxide is removed from the blood, and oxygen is added. The oxygenated blood then leaves the lungs through pulmonary veins and returns to the left atrium, completing the pulmonary circuit.

That’s a lot of responsibility for an organ that’s the size of a fist and weighs less than one pound. It is small but mighty; it never rests. The heart is actually two pumps, not one: one pump (which drives the pulmonary circuit) sends blood to the lungs, where blood is oxygenated, and the second pump (which drives the systemic circuit) sends the oxygenated blood around the body. In the pulmonary circuit, oxygen-depleted blood from the body enters the right side of the heart and then travels to each lung through the right and left pulmonary arteries. In the lungs, carbon dioxide is removed from the blood, and oxygen is added. The oxygenated blood then leaves the lungs through pulmonary veins and returns to the left atrium, completing the pulmonary circuit.

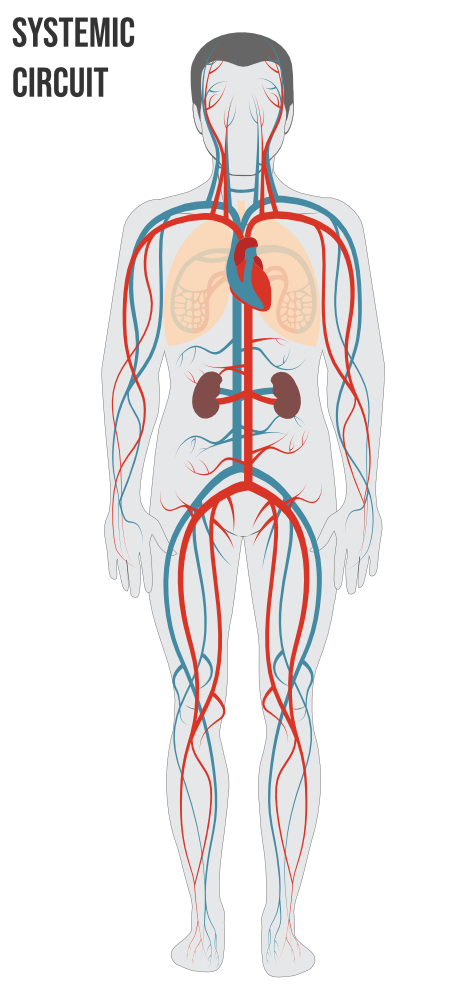

As the pulmonary circuit ends, the systemic circuit begins. In the systemic circuit, oxygenated blood moves through the heart’s left side and is pumped into the aorta, the body’s largest artery. The aorta branches into major arteries that travel to the upper and lower body. The arteries branch into arterioles and then capillaries. On the level of capillaries, metabolic waste and carbon dioxide diffuse out of the cell into the blood, while oxygen and glucose in the blood diffuse out of the blood and into the cell. Systemic circulation keeps up the metabolism of every organ and every tissue in the body. The deoxygenated blood travels back from capillaries to venules, then veins, and finally, the venae cavae, which drains into the right portion of the heart.

As the pulmonary circuit ends, the systemic circuit begins. In the systemic circuit, oxygenated blood moves through the heart’s left side and is pumped into the aorta, the body’s largest artery. The aorta branches into major arteries that travel to the upper and lower body. The arteries branch into arterioles and then capillaries. On the level of capillaries, metabolic waste and carbon dioxide diffuse out of the cell into the blood, while oxygen and glucose in the blood diffuse out of the blood and into the cell. Systemic circulation keeps up the metabolism of every organ and every tissue in the body. The deoxygenated blood travels back from capillaries to venules, then veins, and finally, the venae cavae, which drains into the right portion of the heart.

Systemic circulation is a much larger and higher-pressure system than pulmonary circulation because systemic circulation must force greater volumes of blood farther through the body. Yet the output between the two circuits must be balanced every time; otherwise, the entire system won’t work correctly.

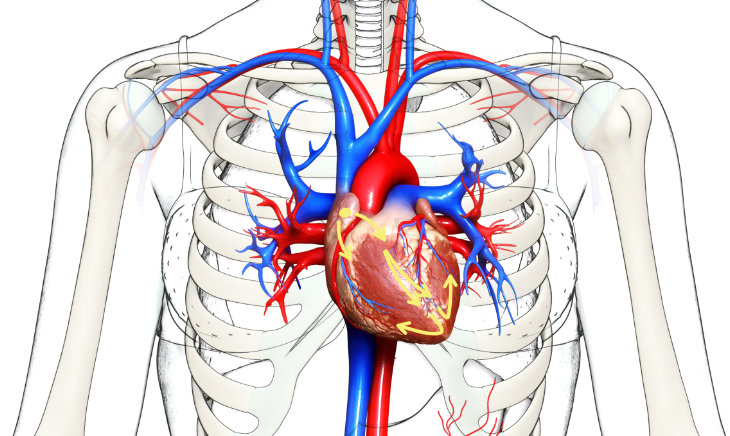

Your heartbeat is the contraction of your heart to pump blood to your lungs and the rest of your body. Your heart’s electrical system determines how fast your heart beats. The SA (sinoatrial) node is a small cluster of cells that generates an electrical signal that causes the upper heart chambers (atria) and then the lower heart chambers (ventricles) to contract. The SA node is considered the pacemaker of the heart. It is located in the wall of the right atrium. Since your heart is positioned slightly to the left, the SA node is located right behind your breastbone. This means that the electrical activity of your heart is initiated in the center of your chest, in the place we commonly call “the heart center.”

Your heartbeat is the contraction of your heart to pump blood to your lungs and the rest of your body. Your heart’s electrical system determines how fast your heart beats. The SA (sinoatrial) node is a small cluster of cells that generates an electrical signal that causes the upper heart chambers (atria) and then the lower heart chambers (ventricles) to contract. The SA node is considered the pacemaker of the heart. It is located in the wall of the right atrium. Since your heart is positioned slightly to the left, the SA node is located right behind your breastbone. This means that the electrical activity of your heart is initiated in the center of your chest, in the place we commonly call “the heart center.”

There are two phases of a heartbeat:

- When the heart contracts and pushes blood out into the body (the systole)

- When the heart relaxes and refills with blood (the diastole)

When your blood pressure is measured, these are the two numbers you get. They show the highest and lowest pressures your blood vessels experience with each heartbeat. A blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg and above is considered too high and raises the risk of a heart attack or stroke. Blood pressure is considered “low” when it’s below 90/60 mm Hg (although it varies from person to person). Low blood pressure might cause no noticeable symptoms, or it might cause dizziness and fainting. In general, blood pressure depends on many physiological and mental-emotional factors and fluctuates throughout the day.

The blood pressure is generally higher in the lower body (thanks to gravity). Your veins contain specialized valves that prevent the blood from flowing backward, and the contraction of your leg muscles helps to pump the blood back up toward the heart. That is why it is essential for your heart health to get up and move often.

Your heart works non-stop, which means that cardiac muscle cells require reliable supplies of oxygen and nutrients. But the heart itself is not nourished by the blood that passes through it; the oxygen it needs to function properly comes from the coronary arteries. When the demands for oxygen increase (during exercise, for example, or any other kind of excitement), the blood flow to the heart through the coronary circulation may increase up to nine times that of resting levels to meet the challenge.

Revving up your cardiovascular system is not that hard. All you need is some stress hormones that activate your sympathetic (flight-or-flight) system, and before you know it, your blood volume is up and roaring through the body with more force and speed, delivering it to the places where it’s most needed. This is a necessary process for us to rise up to challenges in our lives (physical or any other kind). But if you rev up your system this way anytime someone irritates you, it will put undue wear and tear on the system and increase your risk of heart disease. Next time we will look at what chronic stress does to your circulatory system, what we can do about it, and how the vagus nerve factors into it – tune in!

[jetpack_subscription_form]

Resources

-

Fundamentals of Anatomy & Physiology by F. Martini, J. Nath, E. Bartholomew (affiliate link)

-

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson (affiliate link)

-

Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers by Robert Sapolsky (affiliate link)

-

MetaAnatomy: A Modern Yogi’s Practical Guide to the Physical and Energetic Anatomy of Your Amazing Body by Kristin Leal (affiliate link)

I get tons of information from reading your post. Thank you.

Thank you, Maryann; happy to hear it!

So thankful for your articles, return to your home page again and again. Makes me a better yoga teacher for sure!

Tried to find the article regariding Vagus nerve which you refer to in this article, kindly coul you assist me?

Hi Åsa, thank you for your kind words about our site! Here are the posts I wrote about the vagus nerve; I hope that you will find them helpful!

Vital Vagus: What is the vagus nerve and what does it do?

How can we stimulate the vagus nerve in our yoga practice? Part 1

Vagus nerve and sound: Can you “tone up” the whole body?