Polyvagal Theory opens up new ways to interact with our clients and gain understanding to build healthy, caring, therapeutic relationships.

0

by Charlotte Nuessle, C-IAYT, BSc

As a yoga therapist, learning to listen to my nervous system’s signals for regulation, safety and cues of danger has been invaluable in being present with a client. This post will give a simple introduction and explain basic language of the Polyvagal Theory, as a background to enrich a trauma informed practice. Then we’ll explore self-regulation and the conditions needed for it.

Polyvagal Theory was developed by Dr. Stephen Porges. It offers a roadmap that we can predictably apply to the human condition, much as we apply the koshas or chakra model from our yoga tradition. To apply this theory in our work with clients, we need to also reflect on and discover how to bring it into our own lives.

When we’re born into the world, we instinctively seek connection with our primary caregivers. A foundational principle of Porges’ theory is that we have a biological imperative for safe social connection with other humans.

When we’re born, our unique nervous system is brand new. Yet, as one of billions of other humans on the planet, our nervous system evolved over millions of years.

Recognizing this biological imperative can enlighten our way as yoga therapists. Our nervous system takes cues from inside and around us. Our body’s innate intelligence is reliably checking the messages it receives. Deb Dana, LCSW, teaches that our nervous system is asking, “Am I safe?”

When we work with a client who manages trauma, we recognize that essential needs for safety were unmet and were instead violated. Trauma was woven through the body’s responses. The nervous system becomes vigilant about picking up cues of danger. It automatically protects through fight-or-flight and in trauma, through shutting down.

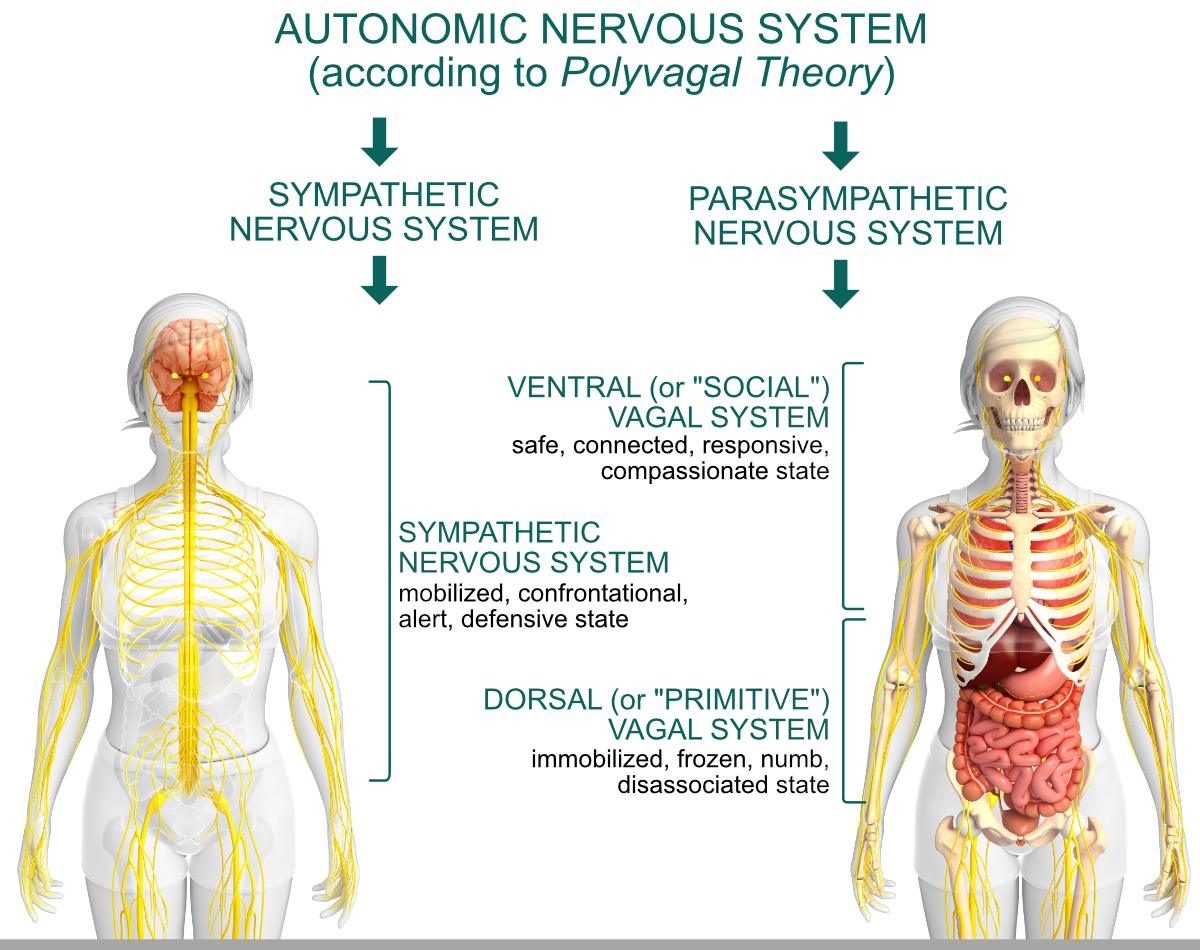

Porges described our autonomic nervous system’s two branches and three states. The two branches are the sympathetic branch and parasympathetic branch. The nervous system has three automatic responses or states, to the information it takes in.

The sympathetic branch is located along the spine in the middle of the trunk. It’s the branch that gets us ready to take action. If our system takes in cues of danger, it pumps adrenaline and shifts into the fight-or-flight response.

The parasympathetic branch has two pathways that are found in the vagal nerve. The vagus nerve is bi-directional. It travels down from the base of the skull through the lungs, heart, diaphragm and stomach. It also travels upward to the neck, throat, eyes and ears.

The vagus has two parts, the ventral vagal and dorsal vagal. The dorsal vagal pathway is recruited when our system perceives acute, intense danger. The ventral vagal pathway recognizes cues of safety and brings the experience of feeling safe enough to connect with others.

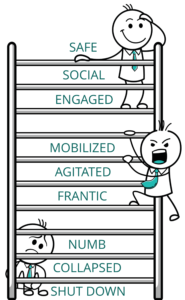

Polyvagal theory describes a predictable way our unique, yet common to us as humans, nervous system move from state to state. As we consider these subtle and not-so-subtle state shifts, relate this to your experience.

When we feel regulated – balanced and open – we’re in a ventral vagal state. This is a place of being present with ourselves and with others. We can take risks, be courageous, we’re comfortable in our own skin. We can step back and have a bigger perspective. Imagine words that name your experience: connected, in a flow, access to wisdom.

When we feel regulated – balanced and open – we’re in a ventral vagal state. This is a place of being present with ourselves and with others. We can take risks, be courageous, we’re comfortable in our own skin. We can step back and have a bigger perspective. Imagine words that name your experience: connected, in a flow, access to wisdom.

However, we need protective states too to engage in life. Signals of danger such as crossing a street in traffic, touching a hot oven, or cultivating kindness while driving – rather than road rage – serve a valuable purpose. They alert us to threat and danger.

Let’s say we were in a ventral vagal state, out for a walk on a beautiful day. Then our system picked up some cue of danger, maybe a sudden noise that was unfamiliar. The cue can be real or perceived. The nervous system shifted into a protective response. The first line of defense is fight-or-flight. It happens so fast, we aren’t even aware of it.

Consider your body’s signals when you shift into a full-blown fight-or-flight response. Many describe it as urgency, feeling driven, controlling. There is a range of anger from irritability to rage. What words describe your experience? Where do you feel this response in your body?

If the fight-or-flight response took care of the real or perceived threat, our nervous system shifted back toward safety. For example, we spoke up about an issue with our friend and it resolved a conflict. We turned off the television instead of watching a violent movie. Our system returned to balance again.

If instead, our system continued to get signals of danger – real or imagined – then it shut down with a dorsal vagal response. Dorsal vagal is our nervous system’s oldest response. Think of a tortoise. It’s unable to get away from a perceived or real danger. Instead, it pulls its legs and head inside its shell. It becomes perfectly still and disappears until danger passes.

Eventually the tortoise will poke its head out a little at first and scan, as if its system were asking, “Am I safe in this situation right now?”

That’s how our system responds when moving out of a protective dorsal vagal state. Slowly, in small steps, to gradually re-establish enough safety to move.

As yoga therapists, this topic is worthy of our curiosity. We can apply Kriya Yoga principles of self-awareness, svadhyaya, and tapas, staying with a line of inquiry, to explore how our own system shifts. Understanding the place for co-regulation, for example that others might see our familiar tendencies more clearly than we ourselves, helps us embody kindness at home. Co-regulation invites us into humility as life learners while we offer care to others.

Perhaps another way to consider ishwara pranidhana might be as a state of self-regulation. Awe and inspiration expand our perspective and experience of connection. Time in nature or meditation might be doorways that bring us to self-regulation. At other times we need safe connection with a human being. We live informed by a nervous system that’s always responding to the cues it takes in. Our aim can be to become more flexible in how our system shifts from one state to another.

During a client session, understanding our own nervous system state and being curious about our client’s, makes us present. We can recognize state shifts, re-align with our intention to be a safe presence for our client and address our personal needs later with curiosity and compassion.

Take away:

1. Become familiar with your nervous system states

2. Brainstorm three simple things to come back to balance when:

- Your system starts to shift into fight-or-flight

- Your system gets pulled into collapse/shutdown

3. Strengthen your capacity to return to ventral vagal state:

- List three things that bring you a sense of safe connection when you are on your own

- List three things that bring you a sense of safe connection when you are with others

Additional reading:

- Deb Dana’s article, A Beginner’s Guide to Polyvagal Theory

- More resources: https://www.rhythmofregulation.com/resources

Check out Charlotte’s Real-Life Case Studies video series on the Sequence Wiz community site. (Available exclusively to Sequence Wiz members. Learn more about Sequence Wiz membership >)

Part 1 (coming this Friday): Looking for cues from the client’s nervous system

We will release Charlotte’s case studies once a week on Fridays; join our Case Studies group to follow along!

[jetpack_subscription_form]

About Charlotte

About Charlotte

Charlotte Nuessle is an internationally certified yoga therapist through IAYT, with BSc in gerontology. She had dedicated almost twenty years to service at Kripalu Center and had offered adaptive yoga/body-based & mindfulness practices in senior living communities. She had been a consultant with AARP Oregon, and Providence Medford Medical Center, and she had guided Trauma Informed Yoga groups for those managing PTSD. Charlotte specializes in working with students who are dealing with issues around age, illness, grief, and death. She’s informed by three wisdom approaches: yoga therapy, resilience and understanding our human nervous system through polyvagal theory. Read more about Charlotte and her work >