How to lengthen your spine without strain

11There are two distinctive ways of lengthening the spine while doing axial extension postures – one that focuses on bringing the spine into maximum vertical alignment, and another one that focuses on integrating all the spinal curves without strain.

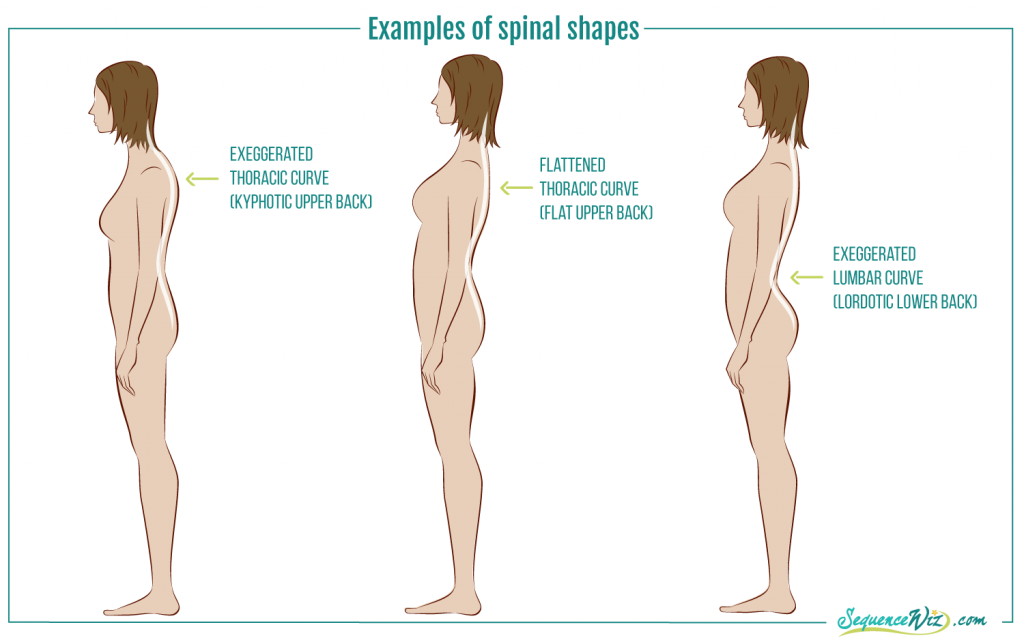

Now before you begin any sort of experimentation here, you need to find out what the shape of your spine is currently. You probably already have an idea if you have an exaggerated thoracic or lumbar curve. If not, stand sideways by the mirror and take a closer look. Or better yet, have somebody observe you and give you feedback. Keep in mind though, that you are interested in the shape of the spine itself, not the surrounding structures. For example, if your shoulder blades tend to “wing out”, it might look like you have a pronounced upper back curve, but this is the shape of your shoulder blades, not the spine. Instead of looking at that, have somebody trace the shape of your thoracic spine with his or her hand and tell you if it feels flat or rounded.

Keep in mind that it’s not like one is better or worse then the other. It’s just that each type has certain tendencies and this is what you have to work with.

Keep in mind that it’s not like one is better or worse then the other. It’s just that each type has certain tendencies and this is what you have to work with.

Once you get an understanding of what your spinal shape is like, you can apply the appropriate recommendations from below.

1. How to bring the spine into maximum vertical alignment.

Lie down on your back, raise your arms up and then stretch in both directions – up with your hands, and down with your feet. This is the simplest representation of the axial extension – you are trying to lengthen the spine. Seems easy enough – stretch on the inhale, relax on the exhale. One thing you will probably notice right away is that your spinal curves change shape when you do that. Your thoracic spine is likely to flatten more (as it always does when you raise your arms up) and your lumbar curve will probably deepen (to compensate for the thoracic curve flattening). By itself this is not a problem; it becomes a problem if:

Lie down on your back, raise your arms up and then stretch in both directions – up with your hands, and down with your feet. This is the simplest representation of the axial extension – you are trying to lengthen the spine. Seems easy enough – stretch on the inhale, relax on the exhale. One thing you will probably notice right away is that your spinal curves change shape when you do that. Your thoracic spine is likely to flatten more (as it always does when you raise your arms up) and your lumbar curve will probably deepen (to compensate for the thoracic curve flattening). By itself this is not a problem; it becomes a problem if:

A. We don’t control the depth of the lower back curve and exaggerate it; or

B. If we do not have a lot of mobility in the thoracic curve and end up straining the shoulders and neck in our efforts to raise the arms all the way up (this is common for folks with kyphotic backs).

What can we do about that?

A. We can focus on progressive abdominal engagement with every exhalation and control how far the pelvis rotates forward.

B. We need to make sure to awaken the thoracic area before we do any poses that require us to hold the arms overhead, especially if we intend to bear weight on the hands.

Quick example: It is problematic for many people to hop into Downward facing dog too soon at the beginning of the class because of the common restrictions in the upper back and shoulders. So it might be useful to do Vajrasana (to warm up the shoulders and begin to move the thoracic spine) and Bhujangasana (to warm up the upper back). Bhujangasana won’t do anybody any good, though, if we mostly bend in the lower back (and many people who have upper back stiffness will do just that). So keeping the hands by the lower ribs and elbows up while pulling (instead of pushing with the hands) will usually help bring some awareness and movement into the upper back. After you do that few times, you will be more ready for the Downward dog and the like.

On the other side of the spectrum, of course, are the folks with flat thoracic curves, who tend to hang on their shoulder joints and almost curve their thoracic spines backwards. This is not a good idea either, since we are not trying to lose thoracic curve altogether (you need it), and it compromises shoulder stability. So in Downward dog, for example, we would avoid pulling the chest toward the thighs and instead focus on breathing into the upper back AS IF you were trying to inflate your thoracic curve and make it more pronounced.

On the other side of the spectrum, of course, are the folks with flat thoracic curves, who tend to hang on their shoulder joints and almost curve their thoracic spines backwards. This is not a good idea either, since we are not trying to lose thoracic curve altogether (you need it), and it compromises shoulder stability. So in Downward dog, for example, we would avoid pulling the chest toward the thighs and instead focus on breathing into the upper back AS IF you were trying to inflate your thoracic curve and make it more pronounced.

As you can see, whenever we practice axial extension postures we need to understand what the shape of our curves is to begin with, and keep a close eye on what the spinal curves are doing when we move AND when we sit (which brings us to the second way of doing axial extension postures).

2. How to integrate all the spinal curves without strain.

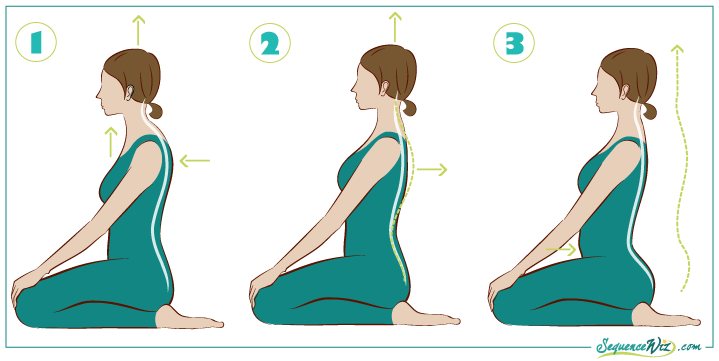

Sit in a comfortable position with your eyes closed and breathe. After you do it for a while, more likely than not you will begin to slouch (exaggerating your thoracic curve) or collapse into your lower back (exaggerating your lumbar curve). To avoid doing that we want to create a sensation of lifting up through the top of the head, but this action is different from the one we described earlier. Here you have an opportunity to fine-tune the position of your spinal curves and support them in a place where they are the most vulnerable.

Sit in a comfortable position with your eyes closed and breathe. After you do it for a while, more likely than not you will begin to slouch (exaggerating your thoracic curve) or collapse into your lower back (exaggerating your lumbar curve). To avoid doing that we want to create a sensation of lifting up through the top of the head, but this action is different from the one we described earlier. Here you have an opportunity to fine-tune the position of your spinal curves and support them in a place where they are the most vulnerable.

1. If your thoracic curve is very pronounced, every time you inhale lengthen up and try to flatten your thoracic curve a bit while lifting the chest up. Make sure that this action doesn’t affect the lower back curve.

1. If your thoracic curve is very pronounced, every time you inhale lengthen up and try to flatten your thoracic curve a bit while lifting the chest up. Make sure that this action doesn’t affect the lower back curve.

2. If your thoracic curve is flat, avoid pulling the shoulder blades down and instead inhale into your upper back AS IF you are trying to make your thoracic curve more pronounced. Your inner body sense might start screaming “I am not upright, I am slouching!” Comfort it by lengthening upwards through the top of your head as you inhale, at the same time inflating your upper back.

3. If you tend to collapse into the lower back curve, make sure to progressively contract your abdomen as you exhale and create the sensation of lifting upwards all along the spine when you inhale.

All those details might seem subtle and insignificant, but they make a huge difference in the way your body learns to support itself. And axial extension postures give us an excellent opportunity to focus on the spinal alignment. Once you get yourself to a place where it requires less effort to stay aligned and upright, it will make it easier on your body in your daily life and it will help you spend more time on breathing and meditation in your yoga practice with minimum bodily discomfort. And this is what yoga is ultimately about, right? ☺

Good morning Olga,

Great article as always. Could you also use male bodies occasionally. The yoga community is lucky to have you.

Yours respectfully,

Georgeanna

Thank you Georgeanna! I would love to use images of males doing yoga but unfortunately those are much harder to come by 🙁

Thank you for providing much-needed insight and guidance in helping to understand how our spine works and what we can do to get more from our practice. As someone who has had his share of “back issues,” this and other postings on the spine have been especially invaluable in my recovery efforts. Thanks again.

Olga, I truly cannot express how grateful I am for your continued guidence, from the bottom of my heart….

Hi Olga, I have a very flat lumbar curve. Any advice for this?

Hi Jen! The flatness of the curve is usually not a problem in itself, unless you begin having issues elsewhere: lower back, hamstrings, tailbone, etc. If you do have discomfort in one of those areas, then flat lumbar curve could a factor and should be addressed as part of your treatment plan. The best thing you could do is work on establishing a functional pelvic-lumbar relationship, it helps resolve so many issues!

Thanks Olga!

Due to an injury (old) C 5-6-7 are fused and because of that my head will not rest on the mat when lying flat, nor will my arm reach the floor if I were to stretch them overhead. I am an avid Yogi and my question is does this affect the advice you have for a Kyphotic thoracic spine. I am a senior citizen and have being doing Yoga for about 14 years

Olga — you always have the best articles! Thank you for sharing your wisdom.

Thank you Kacie! 🙂

The spine is recognised as possessing an intrinsic intelligence. Beyond the concept of an ideal alignment, which is important when identifying underlying postural issues, is the notion that movement and exercise should be in part designed to encourage a full ‘motility’ to the spine. Once the barriers of poor usage, weakness, or over development of certain muscle groups are addressed, the spine can be ‘educated’ as to the full range of flexibility and mobility available to it with the overarching understanding, that it is capable of ‘taking it from there’ when achieving ideal alignment.

Central to this approach is the concept of discipline leading to disengagement of intrinsic tensions which may be the result of poor exercise regimes, sedentary lifestyles, work patterns, and general or specifics anxieties.